If you read the first CREATURE FEATURE, then you might remember the mention of a curious thing called a “Protist.” Unfortunately, most people that aren’t biologists (or way too deep into edu-tainment youtube) don’t know what protists are! For shame, lackluster public school science programs! For shame.

Not to say that I don’t kind of get it. Lots of kids (and adults, for that matter) struggle with the basic plant, animal, and fungus classifications, so why throw protists into the mix? It’s not like they’re relevant to our everyday lives or incredibly important for sustaining almost All Life on Earth or anything…

Wait.

Hold on, I’m getting a report from my correspondents on the ground.

Oh, really? Wow. Okay, I’ll tell them.

Yeah, as it turns out that the majority of the oxygen that gets produced on Earth comes from protists, not plants. Exact numbers depend on who you ask, but everybody can agree: if there weren’t any protists, there would be way less oxygen for animals like us to breathe. It’d be bad news!

I’m sorry, I’m beating around the bush here. This CREATURE FEATURE isn’t even about a photosynthesizing protist. I’m just very passionate about how cool protists are. How about this? I’ll talk about diatoms in an upcoming Feature. Probably not the next one after this, but one that’s still not too far in the future. Diatoms are cool. They’re photosynthesizing protists. They’re made of glass. Are you getting excited? Please get excited.

Anyways, I hinted at it earlier, but didn’t actually properly define what a protist is. To put it simply, a protist is a eukaryote that doesn’t fit neatly into the category of plant, animal, or fungus. They aren’t really a distinct group based on shared features and evolutionary histories, as is the case with the main three. Instead, they’re more like an “other” category. Two protists might be different as can be, but that’s what happens when you group based on what they’re not as opposed to what they are.

Fun fact, the most famous protist is kelp! That’s right, kelp is not, as it turns out, a plant like you probably thought it was– not that anyone would blame you. They certainly look like plants, after all, but evolved completely separately and lack many plant-y features, such as roots that absorb nutrients.

…I’ve just realized that I’m nearly a page into this Feature (I draft on google docs) and haven’t even mentioned the type of organism it’s meant to be about. And I have A LOT to say about the type of organism it’s meant to be about. That’s my bad. I just think protists are really cool. As I have made clear.

The type of organism we’re supposed to be discussing today is the one, the only, the legendary Plasmodial Slime Mold! Also called a myxomycete (a word that I love saying. Give it a try. Out loud, right now. “Mix-oh-my-seat,” if you weren’t sure) or myxogastrid (I don’t love that one so much. “Gastrid” makes me think of like… gastro-intestinal… bleh).

Now, don’t get it twisted. Just because it has “mold” in the name, that doesn’t mean it’s a fungus. Scientists thought they were fungi for a while, but that is no longer. Remember, these are protists, the super-cool fourth thing.

And, listen, I know I have a tendency to use words like “awesome” pretty lightly, but when I say myxomycetes are awesome, I really mean it. Myxomycetes are awesome.

© John Carl Jacobs

The first thing you should know about all slime molds, not just the plasmodial type, is that they are single-celled organisms.*

Whaaaat? I hear you saying, there’s no way that something of that shape and size could possibly be just one cell!

Well, dear reader, it’s true. Even though some individual slimes can grow to be over three feet long, and weigh more than twenty-five pounds, they are just one giant cell. Normally, this shouldn’t be possible, but plasmodial slime molds discovered a little cheat code: make a butt load of nuclei, stick them anywhere you can find room, and suddenly you don’t need individual cells anymore! Remember, nuclei hold DNA, and DNA holds the instructions for making the proteins that keep an organism functional. Therefore, so long as it has enough nuclei to produce enough proteins to support the whole body, the slime mold has no reason to wall off these nuclei into their own individual cells.

As a result of this strange structure, plasmodial slimes can’t develop organs– you need cells to do that! Their entire bodies are more-or-less uniform, which allows them to move in some frankly incredible ways.

© Heather Barnett

When you don’t have any legs or even muscles, it turns out the best way to move around is to hurl your insides in the direction you want to go.

I’m only exaggerating a little bit.

If we think of cells as essentially being more complicated bags of goo, the “bag” part is called the cell membrane, and the “goo” part the cytoplasm inside. The cell membranes contain a structure made of proteins that contract, pushing the cytoplasm forward.

(Fun fact: they’re the same proteins that let human muscles contract!)

When the cytoplasm gets pushed forward, it bumps that part of the slime just the teeniest tiniest bit forward. Then, it has to move back again so it can get another “running start,” so to speak. This back-and-forth strategy is what creates the distinct pulsating we can see in on-the-move myxomycetes.

Of course, all of this happens veeeeery sloooowly. If you were to find a slime mold outside, it would look totally stationary. No movement at all. The top speed of the fastest slimes is still only centimeters per hour.

Perhaps because of these slow speeds, slimes need to be Smart about where they go. This leads us into what very well may be the most iconic feature of the myxomycete…

© Steve Young

… the tube network!

When a slime gets hungry and wants to search for food, it could just move in some random direction and hope for the best, or it could expand in every direction, but this would take quite the bit of energy, and it’d be quite literally spreading itself thin. Instead, it takes up a sort of in-between strategy, tentatively fanning out to cover a wide arc at once.

The bits of the fan that happen upon something yummy keep pressing on in that direction, meanwhile the bits that happened upon something not-so-lovely contract back in.

The visual result of this is a bunch of intersecting tubes showing us exactly where the slime wants to be.

© Matt Meadows

Now, when the slime retracts, it leaves a little chemical trail behind. This way, if a slime starts to fan out and finds the trail it left, it knows “My oh my, I’ve already been here, and I found out it was no good! Best try a different direction!

This simple strategy means that the slime is able to compare multiple paths, and select which one is better based on past experiences. Over time, it will shrink from a fan into tubes connecting whichever bits of food it found, resulting in a highly-efficient network of pathways– which is just incredibly impressive for an organism that doesn’t have a brain!

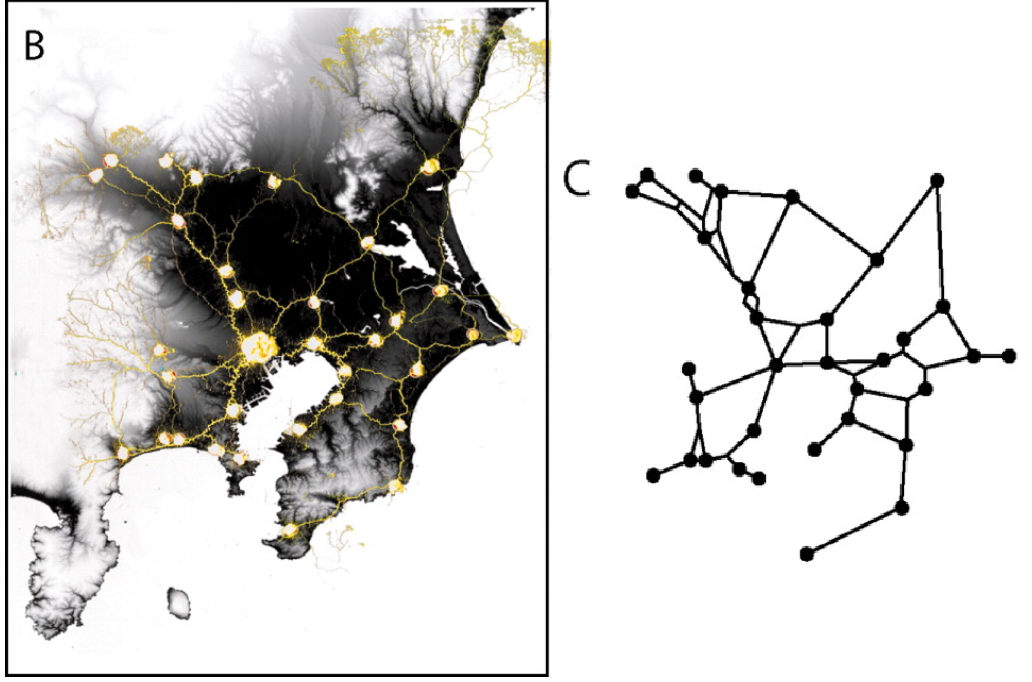

In 2010, some researchers in Japan decided to really put these pathfinding capabilities to the test.

(if you’re a myxomycete fan, you’ve heard this one a million times before.)

Basically, they set up 36 bits of food (probably oats, but the paper doesn’t clarify) positioned like 36 major train stations in-and-around Tokyo, then shined a light everywhere a train couldn’t go, such as bodies of water or steep terrain, then dropped a slime in and let it go wild!

The little guy quickly got to work exploring, and upon finding the snacks the scientists left for it, concentrated its body into little tubes connecting them, while simultaneously avoiding the lit-up areas, since slime molds don’t much like light.

© Atsushi Tero et al

The final path the slime came up with ended up being just as efficient as the real rail network in this region. Something without a brain accomplished, in only about a day, something that a bunch of super-smart humans have been developing for over a hundred years— isn’t that amazing?!?

Not only can they solve complex logistical problems, but slimes have also been able to adapt to obstacles, and then pass on what they learned in a pretty interesting way.

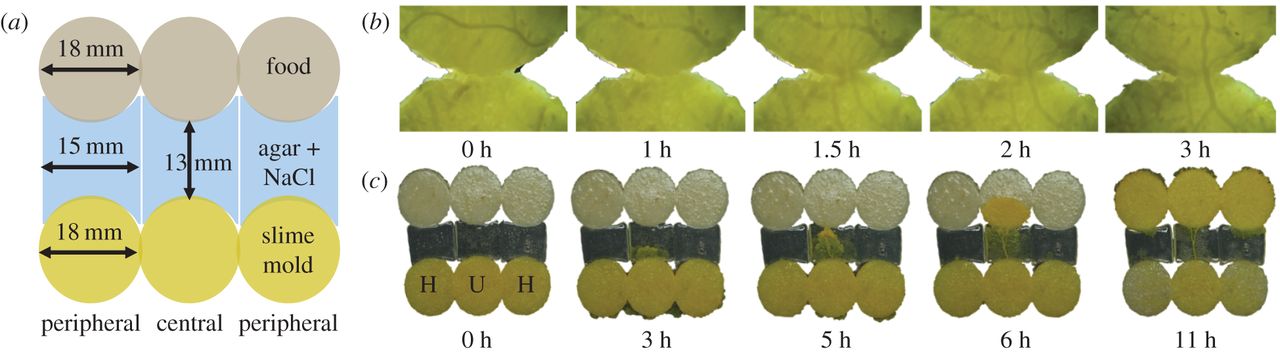

The experiment started off by simply having slimes in a petri dish cross a “bridge” to get to another petri dish, which had some food. This was no problem– slime molds have been able to solve mazes, after all, so one measly bridge is nothin’ for these guys.

Afterwards, the slimes were separated into two groups. The first group just kept crossing the bridges as per usual, but the second group was provided with bridges covered in a salty solution. Slimes don’t like salt so much, and will move away from it if they’re able, but in this case, they didn’t have much of a choice; crossing was the only way to get a meal. At first, the slimes really didn’t like this set-up, moving over it at half their usual speeds, but over five days the set-up was repeated, and every day they got more and more used to the salt, until by the fifth day they were moving at close to their usual speed.

Then, they rested for a few days, and met back up with the group that never encountered the salt bridges.

Then, the salty slimes and regular slimes were allowed to merge– slimes can fuse, by the way, more on that later– before having to cross yet another salt bridge to get to some food.

© David Vogel & Audrey Dussutour – H and U are for “habituated” and “unhabituated.” The habituated slimes represent the salty group.

Despite being composed of both salty and regular slimes, the new fusion-slime was still able to cross the salt bridge as if it had gotten used to it itself. In the above image, it was even the part that used to be a non-salt slime that extended up towards the food source, physically demonstrating the transfer of knowledge.

This experiment was repeated, except the slimes were separated again after mingling for a few hours, but the results remained the same– even the slime molds that had never encountered a salt bridge before could be “taught” to traverse one by a slime with experience.

Conclusion of this section:

Plasmodial slime molds are real smart. And they make for some pretty good teachers!

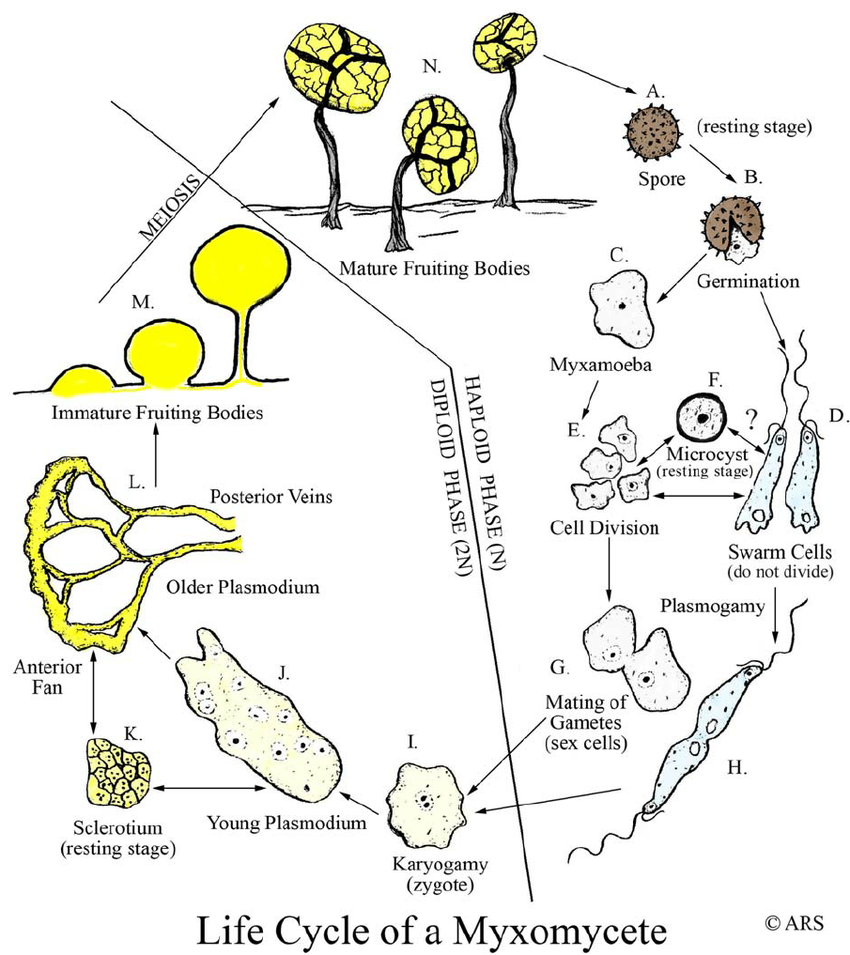

Just like every other aspect of these guys, a myxomycete’s life cycle is super odd! It all begins with a spore, from which a very teeny-tiny little slime (called an “amoeboflagellate”) emerges, hatching as if from a very teeny-tiny egg.

When they start off, they’re microscopic– or, you know, the size a single-celled creature usually is. Depending on environmental conditions, they can either be relatively rigid and flagellated (having little tails that helps them move), or behave like amoebas, resembling a tiny version of their grown-up selves. These baby slime molds are pretty standard single-celled organisms; like I said before, they’re tiny, but they also crucially have only one nucleus (also containing only one set of chromosomes), which seriously limits their growth. Adult slime molds could solve this no-problemo by just splitting up the one nucleus into many nuclei, but babies can’t really do this yet. If a baby wants more nuclei, it has to find a friend to essentially fuse with, so two individuals become one. It is only at this point that the slime can begin to split up its nuclei and start to get big.

© Angela R Scarborough

Now, if you paid good attention in your high school biology class, this whole process might sound awfully familiar. Two cells with only half the usual amount of chromosomes fusing into one cell that can split up in some way? Isn’t that just plain-old sexual reproduction?!

And– it is! This stage (lettered G and H in the above image) is considered to be a stage of the reproductive process, which is just… ?!?!!?!? All the articles and papers I’m reading behind the scenes here just completely gloss over it as if it isn’t freaking WILD!

Like, seriously, is it not absolutely crazy that slimes reproduce this way? Basically having to do it twice?? And, depending on the species, the babies might live for WEEKS before mating, so it’s hardly a temporary thing.

Do I just not know enough about reproduction methods? You only ever really hear about how animals do it, sometimes plants, and it’s never this strange! Maybe this sort of tomfoolery is actually super common if you think about life as a whole, and they just don’t tell you about it.

Who knows. I don’t. Not right now, that is. I will know one day.

Anyways, that tangent over.

After two slimes fuse into one slime, it goes about its slime-y live, creeping around, eating mainly detritus (dead leaves and stuff like that) and bacteria, being totally genius… you know, the works. Then, when the time is right (that is to say, the slime is in DIRE STRAITS), it’ll move into the main part of the reproductive stage.

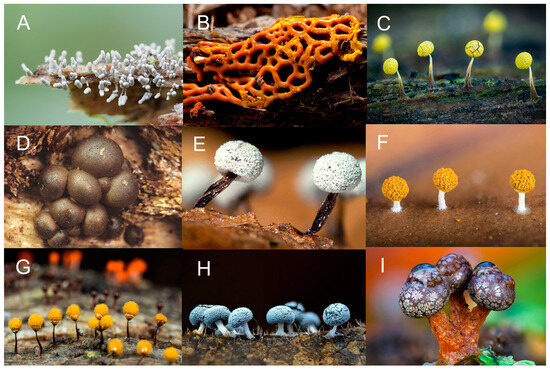

Depending on the species, it may grow stalks topped with spore-producing “fruiting bodies,” or simply appear to puff up, keeping the tube structure. Then, it will release a bunch of little spores, from which a little amoebae will emerge, and the whole thing starts all the way over.

© Steven L Stephenson

There’s so much to say about myxomycetes, and I can only hope to scratch the surface. That being said, there could be something blindingly obvious that I forgot, so I super encourage you to do more research on your own! There’s always something new to learn with these guys.

* Oh, hi! You’re actually following up on that asterisk, way back near the start of the Feature? I shan’t even jest about it, I think it’s great that you’re curious!

This “footnote” is much too long for the main page, so click here if you wanna read about multi-cellular-ish slimes :)